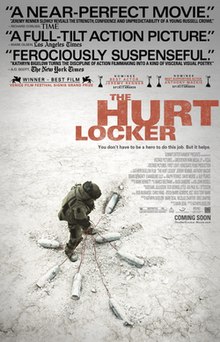

Pretty much the bottom line is if you are in Iraq you are dead. The second year of the Iraq War. A U.S. Army Explosive Ordnance Disposal team with Bravo Company led by Sergeant J.T. Sanborn (Anthony Mackie) identifies and attempts to destroy an IED (improvised explosive device) with a robot but the wagon carrying the trigger charge breaks. Team leader Staff Sergeant Matthew Thompson (Guy Pearce) places the charge by hand, but is killed when an Iraqi insurgent in a nearby shop uses a mobile phone to detonate the charge. Squad mate Specialist Owen Eldridge (Brian Geraghty) feels guilty for failing to kill the man with the phone. Staff Sergeant William James (Jeremy Renner) replaces Staff Sergeant Thompson. He is often at odds with Sergeant J. T. Sanborn because he prefers to defuse devices by hand and does not communicate his plans, removing his headset to prevent communications. He blocks Sanborn’s view with smoke grenades as he approaches an IED and defuses it only moments before an Iraqi insurgent attempts to detonate it with a 9-volt battery. In another incident, James insists on disarming a complex car bomb despite Sanborn’s protests that it is taking too long; James responds by taking off his uniform headset and ‘flipping off’ Sanborn, saying if he’s going to die he might as well be comfortable. Sanborn is so worried by his conduct that he openly suggests killing James to Eldridge while they are exploding unused ordnance outside of base. On their return to base, they encounter five armed men in Iraqi garb by an SUV which has a flat tyre. After a tense encounter, James learns they are friendly British mercenaries (aka ‘private military contractors’) led by a handsome supposed crack shot (Ralph Fiennes). While fixing the tyre, they come under sniper fire. Three of the contractors are killed before James and Sanborn take over counter-sniping, killing three insurgents. Eldridge kills the fourth who attempts to flank their position. During a raid on a warehouse, James discovers a ‘body bomb’ he believes is Beckham (Christopher Sayegh), the Iraqi boy who sells him porn DVDs and plays soccer outside of base. During the evacuation, Lt. Colonel John Cambridge (Christian Camargo), the camp’s psychiatrist and Eldridge’s counsellor, is killed in an explosion; Eldridge is more deeply traumatised. James sneaks off base with Beckham’s apparent DVD sales associate at gunpoint in his truck, telling him to take him to Beckham’s home. He is left at the home of an unrelated Iraqi professor who tells him in English he is pleased to meet someone in the CIA and when his wife attacks James he flees. Called to a petrol tanker detonation, James decides to hunt for the insurgents responsible nearby. Sanborn protests but when James begins a pursuit, he and Eldridge follow. After they split up, insurgents capture Eldridge. James and Sanborn rescue him, although Eldridge gets shot in the leg … You are now in the kill zone. Independently directed and produced by Kathryn Bigelow with a screenplay by freelance writer Mark Boal who had been embedded in the war zone in 2004, this is a relentless, fully immersive trawl through a parched, sunblasted bombscape with three men whose differing takes on their shocking reality lend this an unparalleled realism. The management of the narrative is supreme. Episodic by nature, with six roughly fifteen-minute scene-sequences demarcated by alternating forms of action and different kinds of explosive and disposal style, the contrast between the characters and their various predilections or weaknesses exhibited in their dealings with each other and situations are heightened by the escalating violence, repetition and juxtaposition. Killing off a major star is an appropriately Hitchcockian start in a story that is structurally suspenseful. In comes Renner as James, a wild man who earns the admiration of a vicious commander Colonel Reed (David Morse in one of a number of notable cameos) who sees a guy after his own take-no-injured-prisoners (literally) heart. Sanborn’s ire is juxtaposed with Eldridge’s increasing fear, handled maladroitly by a Yalie shrink whom he inadvertently invites to finally see some action – and boy does he get his after engaging in a dumb talkshow with the local terrorists. This is what we think of psychology/psychiatry – we are in a film where the right wrench is more useful than trying to rationalise the unspeakable violence of modern warfare. When the scene changes and the guys encounter the mercenaries led by Fiennes out in the desert they form a tight trio – right after Sanborn has been conspiring with Eldridge to kill James, who invariably calms things and they are rewarded with a sunset after an exhausting thirsty day of picking off the Iraqis. That happens at 65 minutes and they finally let rip back at base where Eldridge finds James’s memory box of bomb parts that didn’t kill him under his bed. It’s a bonding experience which culminates in a bout of roughhousing between James and Sanborn in which the latter comes off much worse. They discover that James has a wife and son (he’s not sure if he’s divorced) and Sanborn wants that for himself. The scene shifts and another element is finally introduced – water: on the floor of a building where they find a dead boy rigged up with a body bomb and James exhibits emotion believing him to be Beckham, the teen chancer who sells him porn outside the base. A really good bad guy hides out in the dark. Then there’s a massive explosion which results in a cauldron of fire with James believing that it was done remotely and the bomber is likely just beyond the kill zone. So he and Sanborn and Eldridge set off into the nighttime streets in uniform – a difference to the preceding evening when he went out looking for Beckham’s home as a civilian and getting beaten up by that Iraqi woman for his trouble. He shoots Eldridge – accidentally? He’s the one who’s been keeping him sane, now Eldridge has a reason to go home, falling apart physically with a busted femur just as he’s been falling apart mentally with a broken mind. Sanborn stands in a shower and does it in his uniform, collapsing in grief, adrenaline rushing out of him. Then there’s a different kind of bomb – and another variety of conflagration. Back home, shopping in the supermarket, playing with his baby, cleaning the gutters, James tells his wife Connie (Evangeline Lilly) the military needs more bomb techs. And there’s a circular conclusion, like a hero’s journey tale. Bigelow says it’s about the psychology behind the type of soldier who volunteers for this particular conflict and then, because of [their] aptitude, is chosen and given the opportunity to go into bomb disarmament and goes toward what everybody else is running from. Unfailingly tense and suspenseful, this is never less than subjective. And there goes Renner, like an astronaut in his dirtbound bombsuit, walking alone, into a moral void. This was shot by Barry Ackroyd using four 16mm cameras at a time, in Jordan and Kuwait. Two hundred hours of material were edited by Chris Innis and Bob Murawski with a score by Marco Beltrami and Buck Sanders. Simply stunning filmmaking, rivetting storytelling, anxiety-inducing, utterly compelling. Bigelow became the first woman to win the Academy Award for Best Director while the film got Picture, Original Screenplay, Sound Editing, Sound Mixing and Film Editing. A modern masterpiece. Going to war is a once in a lifetime experience. It could be fun!