Aka Dolor y gloria. I don’t recognise you, Salvador. Film director Salvador Mallo (Antonio Banderas) is ageing and in decline, suffering from illness and writer’s block. He recalls episodes in his life that led him to his present situation – lonely, sick – when the Cinematheque runs a film Sabor he made 32 years earlier with actor Alberto Crespo (Asier Etxeandia) and they haven’t spoken since due to the performer’s drug use. But now Salva is in pain and following the reunion with Alberto prompted by his old friend Zulema (Cecilia Roth) will take anything he can including heroin to ease his pain from multiple disabling illnesses. He recalls his mother Jacinta (Penelope Cruz) working hard to put food on the table; moving into a primitive cave house; his days as a chorister whose voice was so beautiful he skipped class to rehearse and got through school knowing nothing, learning geography on his travels as a successful filmmaker. Now he is forced to confront all the crises in his life and his mother is dying … Writing is like drawing, but with letters. Pedro Almodovar’s late-life reflectiveness permeates a story that must have roots in his own experience. His protege Banderas gives a magnificent performance as the director pausing in between heroin hits and choking from an unspecified ailment to consider his path. The stylish visuals that often overwhelm Almodovar’s dramas are used just enough to textually express the core of the film’s theme – love, and the lack of it. Life is just a series of moments and they are recounted here with clear intent, plundering the past in order to reclaim the present. A triumph. Love is not enough to save the person you love

Category Archives: Addiction

The Souvenir (2019)

You are lost and you will always be lost. London, 1980. Shy Knightsbridge-dwelling film student Julie (Honor Swinton Byrne) gets involved with a mysterious older man Anthony (Tom Burke) who claims to work for the Foreign Office. While she starts working on a project and he disappears from time to time, she doesn’t suspect what is revealed at a dinner party by a guest – that he’s a junkie. When he steals all her belongings to score she appears to be reeled in to a deeper relationship with him. She doesn’t socialise as much with her old friends but they visit each other’s parents. Then following a trip to Venice when he realises she is aware of his habit she starts bringing him to housing estates to buy drugs and finally sees what is going on in his life until finally she sees him out of control … Don’t be worthy, be arrogant. It’s much more sexy. Writer/director Joanna Hogg’s quasi-autobiographical tale turns on the passivity rather typical of her characters, upper middle class types stuck in situations they can’t quite recognise and then have trouble leaving. Here it’s a story of her own youth when she fell in with a much older man who concealed his serious heroin problem from her and given the prevalence of that drug among the arty set in the era (read Will Self on the subject) her naivete is somewhat hard to credit. Realism is introduced by a very welcome soundtrack of songs by bands like The Pretenders and The Fall with those awkward dinner conversations punctuated by political talk – the IRA, the Middle Easterners holed up at the Libyan Embassy: we even get to re-live the bomb that ended that particular siege. There are urgent exchanges about movies. Then there are the barely comprehensible phone calls. The letters we can’t read. It is amusing to see Swinton Sr. turning up in twinset and pearls – definitely not how she spent the Eighties, after all, with her forays in Derek Jarmanland. But it takes 83 minutes for Julie to do something active to end the relationship and it’s only when she sees Anthony’s drug paraphernalia at the flat and then he appears, strung out. That’s a long time after he robbed all her possessions for a fix. She may be rather innocent in that sense but she has big ambitions and continues with her film: her obvious class status arises only when her Head of Production comments rhetorically, I don’t suppose you really have to think about budget in Knightsbridge, do you. Richard Ayoade gets a great scene when he obnoxiously ponders how a heroin addict and a Rotarian got together and Julie is utterly baffled: she doesn’t know what track marks are. The photo of Anthony in full beard in Afghanistan circa 1973 didn’t arouse any suspicions. For such a sophisticate you have to wonder, don’t you. The formation of an artist is tough to put together in the frustrating first hour but somehow in the second, it works, when you finally get intimations of an emotional undertow about to burst in a film that is chiefly of memory rather than strict narrative or depth psychology. I do what I do so you can have the life you’re having

First Love (2019)

Aka 初恋/Hepburn/Hatsukoi. It’s all I can do. One night in Tokyo, a self-confident young boxer Leo (Masataka Kubota) who was abandoned as a child and Monica aka Yuri (Sakurako Konishi) a prostitute hallucinating her late father for want of a fix get caught up in a drug-smuggling plot involving organised crime, corrupt cops and an enraged female assassin Julie (Becky) out to avenge the murder of her boyfriend who may or may be betraying his bosses. Kase (Shota Sometani) is desperate to ascend the ranks and kill whoever crosses his path to help his ambition but is plotting a scam with corrupt cop Otomo (Nao Omori) while the gang has to take on the Chinese but are unaware Otomo has infiltrated their ranks … I’m out to kill! Everybody let’s kill! A typically energetic, funny crime thriller from Japanese auteur Takeshi Miike, with an abundance of identity confusion, revenge, astonishing and surreal violence, savage humour and romance. The kind of film where the line Trust in Japanese cars is delivered with utter seriousness. Quite literally a blast from start to finish with bristling action, beautiful night scenes in neon-lit Tokyo captured by Nobuyashu Kita and brilliantly handled action. Written by Masaru Nakamura and produced by Jeremy Thomas. Still things to do before I die

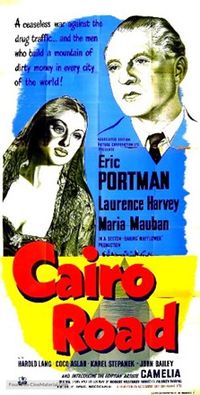

Cairo Road (1950)

Aka El Tariq ela el Qâhirah. They’re alive – but they’re dead. New assistant narcotics agent Lieutenant Morad (Laurence Harvey) gets the jump on a hashish deal following the murder of a local big shot. The team is led by a rather sceptical Colonel Youssef Bey (Eric Portman) the chief of the Anti-Narcotic Bureau who is forced to indulge the new guy’s enthusiasm. Morad has recently relocated from Paris with his wife Marie Maira Mauban) who has to adjust to the new city and worries her husband is putting himself on the line. The team tries to prevent shipments of drugs crossing the southern Egyptian border. They are constantly on alert as even camel caravans are suspect in smuggling narcotics. The agents are investigating the murder of a rich Arab businessman named Bashiri. Raiding a berthed ship in the harbour of Port Saïd leads them to the trail of heroin smugglers, including Rico Pavlis (Harold Lang) and Lombardi (Grégoire Aslan). One of the police agents, Anna Michelis (Camelia) is targeted by the smugglers on board the ship. Eventually Pavlis turns on his partner, killing Lombardi, but Youssef sets a trap for the Pavlis brothers… You’ve started something today. Surely not corruption in the veddy British Egyptian police force? No, Portman is just tacking his usual dyspeptic swerve through the drama while Harvey is the neophyte whose intentions are good but whose deeds wind up being somewhat misbegotten although he gets to prove his worth at the end. It’s quite something to see Portman bullying a camel-owner pleading for the animal he reared from calfhood. He’s a bad ‘un, though. Poor camel! A wonderful opportunity to see the way that region around Suez is perceived in the post-war era and Oswald Morris’ photography has real depth. There’s also a great international cast with a rare chance to see local film star Camelia (born Lilian Victor Cohen) at work, be it ever so briefly. This was the last film of the socialite turned actress whose life swirled with rumour and gossip (particularly regarding a possible relationship with King Farouk) and whose mysterious death in a TWA flight after this film was made remains the subject of speculation. Watch out for familiar names like John Gregson, Eric Pohlmann, Peter Jones and Walter Gotell has a bit part. An intriguing action movie with car and camel chases and a strong pro-police, anti-drugs message, with the bizarre waiver at the credits’ conclusion, ‘Distributed throughout the world. Except the Middle East.’ Directed by David Macdonald from a screenplay by the estimable Robert Westerby. I trust no one

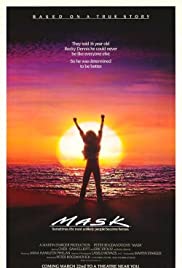

Mask (1985)

I look weird but I’m real normal. Azusa, California. It’s 1978. Roy ‘Rocky’ Dennis (Eric Stoltz) is an intelligent, outgoing and humorous teenager who suffers from a disfiguring facial deformity called “lionitis” and has now outlived his life expectancy: he’s always being told he’s got 6 to 8 months. He’s happy go lucky and indulges his passion for baseball card collecting. His single mother Florence ‘Rusty’ Dennis (Cher) struggles to fight for his acceptance in the mainstream public school system, where he proves himself to be a highly accomplished student at junior high and wins friends by tutoring them. Though Rocky endures ridicule and awkwardness for his appearance, and the classmate he’s sweet on has a boyfriend, he dreams of travelling to Europe with his best friend Ben (Lawrence Monoson). He finds love and respect from his mother’s biker gang family the Turks and particularly likes Gar (Sam Elliott) who eventually reconciles with Rusty and moves in, frequently acting as peacemaker between mother and son. He even experiences his first love when he is persuaded to volunteer at a summer camp for blind kids where he meets Diana (Laura Dern) but then her parents try to keep them separated and Ben lets him down when he says he’s got to move to Chicago ... I want to go to every place I ever read about. Absurdly moving, this wonderfully sympathetic evocation of real-life Rocky Dennis and his mom benefits immensely from being simply told, allowing the characters and the performances to do the heavy lifting. Stoltz has such a tough role but carries it with dignity and aplomb; while Cher is a revelation as the mom whose tough love and wild lifestyle add up to a complex emotional picture. Beautifully written by Anna Hamilton Phelan and sensitively directed by Peter Bogdanovich, this is a life-affirming story of real courage and love. When something bad happens to you you’ve gotta remember the good things that happened to you

Hot Air (2019)

Power down people. The American Dream is dead and buried. You’re dancing on its grave. Conservative radio host Lionel Macomb (Steve Coogan) spends his days broadcasting on hot button topics. His life is completely turned upside down when his 16-year-old niece Tess (Taylor Russell) suddenly shows up, her addict mom, Lionel’s sister, Laurie (Tina Benko) in rehab. His long-suffering girlfriend Valerie Gannon (Neve Campbell) takes her under her wing but the teenager questions everything Lionel stands for and what he believes in while he is in a ratings war with his protegé and rival Gareth Whitley (Skylar Astin) whom Tess unwittingly assists … My job is to make fools look foolish. Steve Coogan’s radio host is a long way from his legendary smug idiot Alan Partridge and yet they have something of a cousinly relationship – a guy who is so cocooned in his beliefs he can’t see the wood for the trees. He needs to be taught a lesson and it comes in the clichéd. form of a relative (and a black one at that) he didn’t really know existed who gives him the opportunity to change a life he didn’t know needed any alteration. Indeed, he has some self-knowledge but what he lacks is sentiment and his unresolved issues from growing up orphaned then abandoned by his feckless older sister have supposedly produced what one protester (and former employee) describes as toxic talk. What does he need to do? He needs to listen. It’s smooth and there are some zingers but it’s not really surprising in terms of linking the personal and the political: the idea that all conservative talk show hosts require is a happy childhood and good parenting to make them decent human beings is a rather naïve skew on the rationale for contemporary partisanship. Right wings hosts using the echo chamber of the airwaves as therapy? If you like: this just doesn’t have the courage of its convictions, if it has any at all. Written by Will Reichel and directed by Frank Coraci. You become the thing you’re running from

Used Cars (1980)

Fifty bucks never killed anybody! Rudy Russo (Kurt Russell) is an unscrupulous car salesman who aspires to become a State Senator for Arizona. In the meantime he works for the nice but ineffective old dealer Luke Fuchs (Jack Warden) with a dodgy ticker selling bangers that die once they leave the lot. When Luke dies in mysterious circumstances, Rudy takes over the business, but he faces stiff competition from his rival across the street, the scheming Roy L. Fuchs – pronounced ‘fewks’ – (also Warden) who wants his brother’s business for himself because he’s paying off the Mayor to put the interstate freeway through the property. Rudy needs to get hold of $10,000 to launch his political campaign. In order to get more customers, Rudy and Roy each devise ever more ridiculous promotions to gain the upper hand. Now it’s every salesman for himself! Then Luke’s estranged daughter Barbara Jane (Deborah Harmon) shows up just when there’s a televised Presidential address to disrupt … They are the lowest form of scum on the face of this earth and I urge you to stay away from them! John Milius gave the idea for the script to Robert Zemeckis & Bob Gale and lo! comedy gold was born in this outrageous tale of oneupmanship, rivalry and sheer chutzpah, a parody of hucksters and a satire about the USA at the tail end of the 70s. Russell and Warden are fantastic. This country’s going to the dogs. Used to be, when you bought a politician the son of a bitch stayed bought! Gerrit Graham, David L. Lander, Frank McRae and Michael McKean are among the brilliant cast where everyone has an angle, even Toby the dog. Screamingly funny, this is one of the best bad taste comedies ever made and simply hurtles to its riotous conclusion taking absolutely everybody prisoner on its mercilessly outrageous joyride. Executive produced by Milius and Steven Spielberg. Nothing sells a car better than a car itself. Now remember this, you have to get their confidence, get their friendship, get their trust. Then get their money

Whitney (2018)

Her parents were preparing her for legacy music. Kevin Macdonald’s documentary about Whitney Houston was made with the co-operation of her family and is executive produced by her agent Nicole David, one of several associates interviewed here, and he has access to the music, so it’s a different creature to Nick Broomfield’s film on the subject, Whitney: Can I Be Me. Macdonald admirably makes this a story of a time and place by dint of regular montages placing us in a year – culturally, socially, politically – with news and current affairs footage and symbols giving a firm context. And it’s jarring to hear Houston’s brother tell us how she got her name – their mother, the famous backing singer Cissy Houston, liked ‘a white sitcom’ on TV so named her for the actress Whitney Blake. Racism of all kinds looms large in this story. Newsreel footage of the Newark riots and the bodies of black men killed by the police remind us of what life was like for black people in New Jersey in the Sixties. Her father John is called both a dealmaker and a hustler, a man who gained powerful status in local circles, and he nicknamed their light-skinned daughter ‘Nippy’ because she was a beautiful but tricky child, and she was bullied in the neighbourhood. She sang in the church choir and sometimes sang backup for her mother who was trying to launch a solo career that didn’t take off. When her parents divorced following her mother’s affair with their church pastor, Whitney left home as soon as possible and moved in with her friend Robyn Crawford who she had met aged 16. Her brothers were aware that Robyn was a Lesbian. One interviewee says that these days Whitney’s sexuality would be designated ‘fluid’ while her longtime hairdresser and friend Ellin Lavar says Houston loved sex, with both men and women and discussed it with her to an embarrassing degree. Whitney modelled but soon sang on her own and two big labels courted her and she signed with Arista’s Clive Davis. He announced her to the world on the Merv Griffin Show and the footage of her singing Home from The Wiz is spinetingling. It is used on the audio track later in a different context in the film, to chilling effect. One contributor talks about the issue of ‘double consciousness’ – the problem that a black entertainer has in having to satisfy a white country and a black world, but in this context it could also refer to Houston’s sexuality and the difference between being Nippy and being Whitney, a stage character. Macdonald does not shirk from the role of the black community – divided on colour lines of its own – and the pressure it exerted on Houston directly or otherwise. In the Eighties, Rev. Al Sharpton appeared in front of her venues with signs calling her ‘Whitey’ Houston (ironically his TV condolences are aired when her death is announced); and of course there is the infamous incident at the 1989 Soul Train awards when the audience booed her – presumably for not being black enough, for having sold out, for singing pop and being brilliant at it. She was asked in an interview why she thought it might have happened – and she claimed she didn’t know. It was the kind of bullying that had provoked her parents into sending her to a private Catholic school in the first place. That was the night she met bad boy (and acceptably black soul singer) Bobby Brown – the ghetto type the Houstons had wanted to keep her away from – and the conclusion is that the couple who would marry and have a child were mutually co-dependent. As her star rose with The Bodyguard, his could never hope to meet it, a year after she had performed The Star-Spangled Banner at the Superbowl, an appearance that still stuns the viewer and nailed her ability and popularity simultaneously when the US was at peak patriotism following the Gulf War. Her Bodyguard co-star, Kevin Costner, was proud of the fact that their interracial kiss was such a significant shot in the film – pointing out the 180 degree camera move, replayed here. (How odd that thirty-plus years after Island in the Sun this should still be a contentious point [and odder still that when he gave a eulogy at her funeral his entrance was greeted with booing by the black attendees – not something mentioned here]. Odder still to a white viewer is Lavar saying that she and Houston were afraid of making the film because they were so outnumbered in the middle of ‘all these white people’: racism is a beat constantly underpinning the narrative.) She was a good actress. I always used to tell them, Whitney’s in there somewhere. But she’s trapped. That film and the theme song I Will Always Love You (written by Dolly Parton) made her a global superstar: she is shown being comforted by Nelson Mandela when she gave the first concerts in South Africa after he came to power. She could find nuance in songs that even the writers didn’t know was there. That record got a British woman gaoled for a week when she drove her neighbours nuts playing it 24/7. An Arab version played endlessly on his campaign trail propelled Saddam Hussein to power. When Brown is asked directly by Macdonald about Houston’s drug use he refuses to discuss it – and perhaps given that it was her own brothers (two full, more half-) who admit introducing her to drugs when she was still a child, he has a point, despite the tabloid headlines about their married lifestyle and on-camera evidence produced here about their home lives (which they eagerly broadcast in their horrifying reality TV show). About two-thirds of the way through the film is the big revelation: her brother Michael volunteers the idea that it’s something in a person’s childhood that drives them to drug use and declares that as a boy he was abused by a female relative. Then Whitney’s aunt says the singer revealed her own experience to her of abuse by the same woman when they were discussing their daughters – this is supposedly why Whitney was afraid to leave Bobbi Kristina (called Krissie) at home while she toured: the same female relative was her cousin Dee Dee Warwick (Dionne’s sister, another singer). Dee Dee is shown in TV clips from the Sixties, a dour-looking heavy-browed character. Bizarrely, Houston is pictured in one home movie lying on a bed under a huge photo of the sinister woman. For all her concerns about her own daughter, Krissie was an unstable cocaine addict by 18 and in and out of rehab, unsurprisingly given what family and friends say she was growing up around [and her own dreadful death, replicating her mother’s, is recounted here]. Houston made a lot of magazine headlines (the National Enquirer alone was running almost weekly updates for a decade) for her drug use; and many more complications arose from 1999 onwards when she signed a $100 million contract for new recordings. By that point she knew her father and accountant had been robbing her blind and her father then sued her – for $100 million. Once her father had taken over managing her there were many members of her family riding the gravy train, other than her mother and Robyn, who was invited to tender her resignation, a decision Whitney endorsed, despite the fact that Robyn had been doing her best to protect her from the sharks throughout her career. I don’t think she knew the layers being created by others. After an excruciating performance in honour of fellow fame victim Michael Jackson, a car crash interview with Diane Sawyer did not help. She had to quit rehab after 8 months because the money ran out. Then there was appalling evidence of her drug-ravaged singing voice in mobile phone footage of one of her last concerts, with one concert goer offering that a dead rat would have performed better. Years were spent pointlessly attempting to record new music, recalled with tragic diplomacy by the producer Joseph Arbagey, who remembers her disappearing for weeks at a time behind her hotel room door and returning emaciated. Many millions of dollars were expended on the fruitless project. No longer fit to perform, she was given a lifeline in a remake of the movie Sparkle, a lodestone film from her childhood that had starred Irene Cara. She played the mother. Her agent says that Whitney had been clean throughout the production and didn’t go home for three or four days after the job was done but at the time she wasn’t aware of it until her driver told her Whitney simply didn’t board the flight and eventually asked him to drive her cross-country to her home. Her agent refers to it as ‘that hole’ in Atlanta. We don’t need to be told what followed. Despite the access, the film still feels curiously incomplete, as if the dots have not been joined: sex abuse, parental ambition and divorce, drugs, Lesbianism, being a light-skinned black in a community divided, being a black singer performing pop songs better than anyone ever had. Cause and effect are not entirely or convincingly linked. Perhaps because this is the official version, unlike Broomfield’s, who talked to Robyn. Or perhaps because the person at its centre had stopped doing what she was good at long before her incredible demise in a bathtub in a Hollywood hotel while her aunt went out to get her donuts with sprinkles and found her dead when she returned just thirty minutes later, as she tells us. The camera enters the hotel room and tracks into the bathroom where Houston was discovered face down in the water. Graced with the voice of an angel in the body of a beautiful black woman exploited by all the people she trusted most in a divided industry produced in a divided country, this biography is a tale of total tragedy, something that regularly occurs in the music business but it’s a story that shows absolutely nobody in a good light, not even Houston herself. It was in every sense a life half-lived. Whitney Houston died 11 February 2012. I’m pissed off. And people think that it’s so damn easy

Midnight Express (1978)

The best thing to do is to get your ass out of here. Best way that you can. American college student Billy Hayes (Brad Davis) is caught smuggling hashish when he’s travelling out of Turkey with girlfriend Susan (Irene Miracle). He is prosecuted and jailed for four years. When his sentence is increased to 30 years, Billy, along with other inmates including British heroin addict Max (John Hurt) and American candle thief Jimmy (Randy Quaid), makes a plan to escape but local prisoners betray their plans to vicious guard Hamidou (Paul L. Smith)… It’s not a train. It’s a prison word for… escape. But it doesn’t stop around here. Adapted by Oliver Stone from Billy Hayes’ memoir (written with William Hoffer), this is a high wire act of male melodrama and violence with an astonishing, poundingly graphic series of setpieces that will definitely curdle your view of Turkey, even knowing that much of this was deliberately fabricated for effect. The searing heat, the horrendous conditions and the appalling locals will give pause to even the most strident anti-drugs campaigner. Director Alan Parker has a muscular, energetic style and brilliantly choreographs scenes big and small with the tragic and brilliant Davis (an appealing latterday James Dean-type performer) perfectly cast and Hurt a marvel as the shortsighted druggie whom he protects. The big scene where Davis totally loses it shocks to this day. Shot in Malta (permission to shoot in Istanbul was not granted, unsurprisingly) by Michael Seresin with a throbbing electronic score by Giorgio Moroder. Everyone runs around stabbing everyone else in the ass. That’s what they call Turkish revenge. I know it must all sound crazy to you, but this place is crazy

Veronika Voss (1982)

Aka Die Sehnsucht der Veronika Voss. Light and shadow; the two secrets of motion pictures. Munich 1955. Ageing Third Reich film star Veronika Voss (Rosel Zech) who is rumoured to have slept with Hitler’s Minister for Propaganda Josef Goebbels, becomes a drug addict at the mercy of corrupt Lesbian neurologist Marianne Katz (Annemarie Düringer), who keeps her supplied with morphine, draining her of her money. Veronika attends at the clinic where Katz cohabits with her lover and a black American GI (Günther Kaufmann) who is also a drug dealer. After meeting impressionable sports writer Robert Krohn (Hilmar Thate) in a nightclub, Veronika begins to dream of a return to the silver screen. As the couple’s relationship escalates in intensity and Krohn sees the possibility of a story, Veronika begins seriously planning her return to the cinema – only to realise how debilitated she has become through her drug habit as things don’t go according to plan … Artists are different from ordinary people. They are wrapped up in themselves, or simply forgetful. The prolific Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s penultimate film and one of his greatest, its predictive theme would have horrible resonance as he died just a few months after its release. Conceived as the third part of his economic trilogy including The Marriage of Maria Braun and Lola, this reworking of or homage to Sunset Blvd., whose ideas it broadly limns, has many of his usual tropes and characters and even features his sometime lover Kaufmann who could also be seen in Maria Braun; while Krohn tells his fellow journalist girlfriend Henriette (Cornelia Froboess) of his experience and potential scoop but Veronika’s hoped-for return is not what he anticipates with a Billy Wilder-like figure despairing of her problem. Its message about life in 1950s Germany is told through the style of movies themselves without offering the kind of escapist narratives Veronika seems to have acted in during her heyday. She’ll be your downfall. There’s nothing you can do about it. She’ll destroy you, because she’s a pitiful creature. Fassbinder was hugely influenced not just by Douglas Sirk but Carl Dreyer and this story is also inspired by the tragic life of gifted actress Sybille Schmitz, who performed in Vampyr. She died in 1955 in a suicide apparently facilitated by a corrupt Lesbian doctor. The unusually characterful Zech is tremendous in the role. She would later play the lead in Percy Adlon’s Alaska-set Salmonberries as well as having a long career in TV. She died in 2011. It’s an extraordinary looking film with all the possibilities of cinematography deployed by Xaver Schwarzenberger to achieve a classical Hollywood effect for a story that has no redemption, no gain, no safety, no love. Fassbinder himself appears briefly at the beginning of the film, seated behind Zech in a cinema. This is where movie dreams become a country’s nightmare. All that lustrous whiteness dazzles the eye and covers so much. Screenplay by Fassbinder with regular collaborators Peter Märtesheimer and Pea Fröhlich. Let me tell you, it was a joy for me that someone should take care of me without knowing I’m Veronika Voss, and how famous I am. I felt like a human being again. A human being!