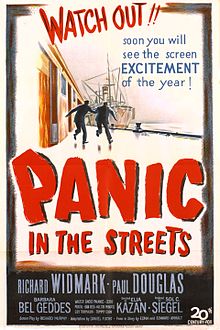

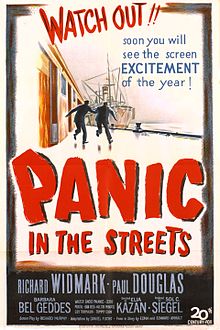

Methuselah is younger than I am tonight. A US Health Service physician Dr. Clint Reed (Richard Widmark) is called to supervise the autopsy of an unknown man and realises the John Doe (actually Kochak and played by Lewis Charles) died of pneumonic plague, the pulmonary iteration of bubonic plague. We have already seen the man chased and shot by the flunkies of gangster Blackie (Walter Jack Palance), Poldi (Guy Thomajan) and Fitch (Zero Mostel) on the dockside. Revealing his discovery to the mayor and city officials, Reed is informed that he has 48 hours before the public will be told about a potential outbreak. Joined by Captain Tom Warren (Paul Douglas), Reed must race against time to find out where the unknown man came from and stop journalists from printing the story so that they can prevent an epidemic. They begin their search among Slav and Armenian immigrants as the man’s body is cremated … From the low level and unwittingly infected crims racing to find the booty they believe the dead man Kochak was protecting, to the warehouses unloading produce on the New Orleans wharves, this paints a great portrait of a city that no longer resembles what we see in this post-war crime thriller. The lurid title only tells you part of the story which director Elia Kazan insisted be shot entirely on location, using the smarts he picked up on Boomerang to create episodes of masterly tension from Bourbon Street in the French Quarter (spot Brennans!) to the banks of the Mississippi, with Reed’s marital and parenting issues nicely etched – there are bills to pay and he should spend more time with his son instead of trying to be more ambitious, according to his wife Nancy, played by Barbara Bel Geddes – providing the day to day humdrum issues against which the bigger melodrama takes place in a race against time. The contrast in performing styles is gripping – from Widmark’s Method-like approach to Palance’s conventional and scary villain, Mostel’s semi-comic goon and Douglas’ usual rambunctious affect to Bel Geddes classical mode, this is a terrific demonstration of American theatre and film acting styles bumping up against each other. It’s beautifully shot by Joseph MacDonald and edited by Harmon Jones. Edna and Edward Anhalt’s story was adapted by Daniel Fuchs and the screenplay is by Richard Murphy but Kazan stated that it was rewritten every day while they were shooting. He would use what he learned of The Big Easy for his next (studio-bound) film, A Streetcar Named Desire. He believed this was the only perfect film he made “because it’s essentially a piece of mechanism and it doesn’t deal in any ambivalences at all, really. It just fits together in the sequence of storytelling rather perfectly. But that’s really why I did it, and I got a hell of a lot out of it for future films.” Very impressive, cher!