Aka Birds of Prey and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn. I lost all sense of who I was. It’s open season on Harley Quinn (Margot Robbie) when her explosive breakup with the Joker puts a big fat target on her back. Unprotected and on the run, Quinn faces the wrath of narcissistic crime boss Roman Sionis aka Black Mask (Ewan McGregor)), his right-hand man, Victor Zsasz (Chris Messina), and every other vile thug in Gotham. But things soon even out when Harley becomes unexpected allies with three deadly women – Helena Bertinelli aka Huntress (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) out to avenge the murder of her entire Mafia family as a child; club singer Dinah Lance aka Black Canary (Jurnee Smollett-Bell) who’s forced to become Mask’s driver; and hot-tempered suspended cop Renee Montoya (Rosie Perez) who’s keen to make her mark in a hostile male environment. And then there’s the tricky street thief Cassandra Cane (Ella Jay Basco) who’s swallowed that diamond with the mob’s bank account details in its mutiple surfaces and that’s what everybody wants most of all … Nothing gets a guy’s attention like violence. The sole bright spark in the otherwise execrable Suicide Squad was Robbie’s Quinn so you can see how she might have wanted to bring this powerhouse character back in a more equitable narrative. The driving force is to get the attention of the man who broke up with her, Joker, but as we know from other films, he’s kinda tied up elsewhere and is quickly forgotten here. The idea of the girl gang that comes to fruition in the final 25 minutes is the MO but intriguingly it’s Harley who needs to be told to ‘focus’ – the other characters are more precisely delineated: the frustrated cop whose throwaway lines are from an 80s cop show, the ingenious pickpocket who unwittingly causes everything, the action babe singer, the highly creative crossbow killer with a serious revenge motive (whose name The Huntress everyone forgets, a nice running joke) which ironically leads to the whole premise being diffused, albeit for a higher feminist purpose. Each of them (bar Harley, who has a penchant for glitter) has a particular fighting style (and the stunts are real something.) McGregor’s psycho villain is thinly drawn and characterised. The fact that the penultimate sequence/showdown takes place in a fun house just exacerbates the cartoonish impact of DC’s all-women superhero squad. Yet it fizzes with antic, frantic, anarchic energy and a sense of its own ridiculousness expressed in many ways but most obviously in the title cards introducing all the characters and the batshit baby doll voiceover. Not to mention that rollerskating Harley’s pet hyena is called Bruce. And yet it’s a story about female empowerment, diversity and righteous vengeance and is all done with effortless humour because Harley ultimately realises their talents are best deployed against their common enemies – scummy men. Robbie is charm itself and channels her inner Marilyn/Madonna with her performance of Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend. Written by Christina (Bumblebee) Hodson, produced by Robbie and directed by Cathy Yan. It almost makes you yearn for Tank Girl and Barb Wire, a pair of female action movies from the 90s that just missed their target. Almost. What a breakup movie – it even has a hair-pulling scene. Well what else would you expect from the fractured psyche of a PhD in Psychology? Girl Power kicks ass! You know, vengeance rarely brings the catharsis we hope for

Category Archives: Marilyn Monroe

What a Way to Go! (1964)

You don’t need a psychiatrist, you need your head examined. Louisa May Foster (Shirley MacLaine), a widow four times over, donates $200 million to the Internal Revenue Service because all her four marriages end in her husbands’ deaths, leading her to believe that the money is cursed and she is a jinx when all she wanted to do was marry for love. She winds up on the couch of psychiatrist Dr. Victor Stephanson (Bob Cummings) who asks her what has led her to do something so crazy and Louisa recounts her life starting with her childhood when her hypocrite mother (Margaret Dumont) preached penury but actually wanted to be rich and berated her poor husband. Louisa dates the richest boy in town Leonard Crawley (Dean Martin) but prefers the little shopkeeper Edgar Hopper (Dick Van Dyke) from high school who refuses to sell out and they bond over Thoreau – until he feels guilty and ends up accumulating huge wealth from non-stop working until it kills him. Then she travels to Paris for the holiday they never took where she encounters part-time taxi driver and wannabe artist Larry Flint (Paul Newman) and inspires him to create moneymaking paintings using machines that respond to Mendelssohn and kill him. She meets maple syrup tycoon Rod Anderson Jr.(Robert Mitchum) who flies her to NYC on his private plane when she misses her flight home and they marry immediately. When he sells up and they retire to a farm he mistakes a bull for a cow in the milking parlour and winds up in a water trough. Dead. Louisa goes for a coffee in a diner and meets Pinky Benson (Gene Kelly) a performer who stars in a terrible dinner theatre production every night. When she persuades him to be himself the crowd loves him, he becomes a star and they go Hollywood where the fans love him to death and Dr. Stephanson hasn’t been listening for the last two husbands … Every man whose life I touch withers. This Betty Comden and Adolph Greene screenplay (from a story by Gwen Davis) proves an astonishing showcase for MacLaine with the film within a film parodies punctuating each marriage providing a great opportunity to send up various moviemaking styles, including silent movies, foreign art films, a Lush Budgett!! spectacular, and culminating in a wonderful musical pastiche with Kelly. It’s a total treat to see these famous dancers performing together (look quickly for Teri Garr in the background!). It’s a breezy soufflé of a movie and a distinct change of pace for director J. Lee Thompson who previously worked with Mitchum on the classic thriller Cape Fear. Very charming and funny with lots of good jokes about the American Dream, the art world, Hollywood and fame, and terrific production values. That’s Reginald Gardiner as the unfortunate who has to paint Pinky’s house … pink. A wonderful opportunity to see some of the top male stars of the era making fun of themselves. Perhaps what’s most astonishing is that this was supposed to star Marilyn Monroe until her shocking death and Pinky’s swimming pool is the one from the abandoned set of Something’s Got To Give. Thompson and MacLaine would work again the following year on the Cold War spoof John Goldfarb, Please Come Home. Shot by Leon Shamroy, edited by Marjorie Fowler, costumes by Edith Head, jewellery by Harry Winston and score by Nelson Riddle. Money corrupts, art erupts

The Cure for the Coronavirus Lockdown, Part 18

Marilyn. Jane. Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953). Perfection.

Ladies of the Chorus (1948)

Her mother is a one-man security council. Single mother Mae Martin (Adele Jergens) and her daughter Peggy (Marilyn Monroe) are Broadway showgirls performing in the same show. But when the lead performer Bubbles La Rue (Marjorie Hoshelle, uncredited) in the burlesque walks out, Peggy finds herself catapulted to overnight fame as the star attraction of the revue. May tries to advise her about people who might try to take advantage of her, including her new socialite boyfriend, Randy Carroll (Rand Brooks) because of a similar experience that befell her back in the day. Peggy falls for him anyway, and he quickly proposes marriage. But he has difficulty telling his own mother (Nana Bryant) about his fiancée’s background and Mae decides against revealing the truth about their showbiz life when the future in-laws finally meet … When are you going to let me feel grown up? Written by Joseph Carole and Harry Sauber, this B movie was Monroe’s first big role and also her ticket out of Columbia Pictures – to looking for another studio contract. While she acquits herself reasonably well in this conventional story of the star is born variety, there is no true sign of the real-life star she would become four years later once she had taken more acting classes and perfected other facets of her screen persona: that performance is yet to be matched to the specific look she would refine to her own inimitable affect and there are a couple of shots of her in repose that are downright unflattering. Nonetheless she gets to demonstrate her singing and dancing chops as the burlesque queen facing a dilemma. Jergens seems crazy young to be her mother (she was nine years Monroe’s senior) but her situation is explained in a flashback and she takes off her wig several times revealing supposedly grey hair beneath, to dramatic effect. Bryant gets to play the equal opportunities mother-in-law who spins a nice ending out of the setup. There’s a frankly odd number involving dolls and an utterly weird entrance by an interior decorator with a small soundalike ‘son’. Directed by Phil Karlson. You’re never too old to do what you did

Under the Silver Lake (2018)

Everything you ever hoped for, everything you ever dreamed of being a part of, is a fabrication. Sam (Andrew Garfield) is a disenchanted 33-year-old who discovers a mysterious woman, Sarah (Riley Keough) frolicking in his apartment’s swimming pool. He befriends her little bichon frisé dog Coca Cola. She has a drink with him and they watch How to Marry a Millionaire in the apartment she shares with two other women. Her disappearance coincides with that of billionaire Jefferson Sevence (Chris Gann) whose body is eventually found with Sarah’s. Sam embarks on a surreal quest across Los Angeles to decode the secret behind her disappearance, leading him into the murkiest depths of mystery, scandal, and conspiracy as he descends to a labyrinth beneath the City of Angels while engaging with Comic Fan (Patrick Fischler) author of Under the Silver Lake a comic book about urban legends who he believes knows what’s behind a series of dog killings and other conspiracy theories who himself is murdered …… Something really big is going on. I know it. Written, produced and directed by David Robert Mitchell who made the modern horror masterpiece It Follows, this is another metatext in which strange portents and signs abound. Revelling in Hollywoodiana – Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, Alfred Hitchcock and Janet Gaynor – and noir and death and the afterlife and the songs that dominate your life and who may or may not have written them, this seems to be an exploration of the obsessions of Gen X. It’s an interesting film to have come out in the same year as Tarantino’s Hollywood mythic valentine Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood and it covers some of the same tropes that have decorated that auteur’s past narratives with a postmodern approach that is summed up in one line: An entire generation of men obsessed with codes and video games and space aliens. The messages in the fetishised songs and cereal box toys and movies are all pointing to a massive conspiracy in communication diverting people from their own meaninglessness, symbolised in the disappearance of the billionaire which has to do with a different idea of the afterlife available only to the very rich. Sam’s quest (and it is a quest – he’s literally led by an Arthurian type of homeless guy – David Yow from the band The Jesus Lizard – straight out of The Fisher King) is a choose your own adventure affair where he gets led down some blind alleys including prostitution and chess games and even gets sprayed by a skunk which lends his character a very special aroma. The postmodern approach even extends to the sex he has – with Millicent Sevence’s (Callie Hernandez) death being a grotesque parody of the magazine cover that initiated him to masturbation. Sigh. Garfield holds the unfolding cartography together but that’s what actors do – they fill in the missing scenes: it may not be everyone’s idea of fun to watch Spider Man having graphic sex scenes and doing things to himself but the audience is also being played. If the objects are diffuse and the message too broad, well, you can make of it what you will. It means whatever you want it to mean (it’s not about burial, it’s about ascension), a spectral fever dream that at the end of the day is a highly sexual story about a guy who wants to make it with the woman across the court yard in his apartment building, no matter how many secret messages or subliminal warnings are in your breakfast or how many Monroe scenes are re-enacted, filmed, photographed or otherwise stored in the minutiae of our obsessive compulsive Nineties brains. So what do you think it all means?

Happy Birthday Marilyn 1st June 2019

Happy birthday, Goddess.

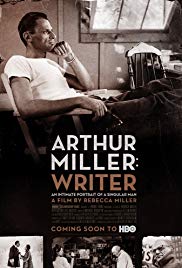

Arthur Miller: Writer (2017)

Filmmaker Rebecca Miller’s documentary about her playwright father is a mesmerising portrait of one of the midcentury’s most important artistes and commentators, utilising home movies, letters, newsreel footage, and interviews she recorded with him and his siblings and her mother and Mike Nichols. Excerpts of Miller’s recording of his autobiography Timebends are interspersed with Rebecca’s own voice to create a narrative. I. Origins. I used to think that a play was about what was between the spoken lines. Growing up with a sub-literate fabric cutter Polish immigrant father and flamboyant, gifted mother, the young Arthur Miller was accustomed to wealth and comfort but that was all removed overnight with the Wall Street Crash when their circumstances were radically reduced. He worked in factories and read Dostoyevsky on the subway and his life was transformed. He wrote plays in college and married a midwestern Catholic democrat and his politics altered from communism to liberalism because he couldn’t see a place for the individual otherwise. She wanted an intellectual, a Jew, an artist. And I wanted America. That’s Miller not describing second wife Marilyn Monroe, but his first wife, Mary. Between the lines you get the sense that for him, relationships were somewhat transactional. His daughter Jane recalls thinking that her conversations with him were material: There were times when he was only interested in something because he could use it. II. Broadway. I knew you were worse than most men, but I thought you were better. Mary was his toughest critic, his first play on Broadway was a failure but his second was All My Sons which he wrote in a wooden hut he built for himself. He wrote the first act during one night, the second in six weeks. Then he sat by the phone, waiting. Nichols states of the work that he believed burned out Miller, It’s so close to the tragedy. It’s so alive. Miller met Elia Kazan and they formed a friendship or even brotherhood that weathered political storms. Kazan introduced him to his on-off lover Marilyn Monroe on the set of the 1951 film As Young as You Feel and Miller told her, I think you’re the saddest girl I ever met. He used the line in The Misfits a decade later when their five-year marriage was combusting. The big thing is not to make simple things complicated but to make complicated things comprehensible. III. Politics. Art is long, life is short. I forgot the Latin. He says Kazan was the greatest theatre director of realistic material and was dismayed by his decision to name names but clarifies that it was the fault of the HUAC as well as the studio that said he would never make films again if he failed to do so. For Miller, the victims experience guilt – about other things. The guilt of the victim was interesting to me. That is the subject of the allegorical The Crucible, in which he memorialises Marilyn Monroe in the character of Abigail while his own wife is personified by John Proctor’s wife, Elizabeth. He met Monroe in 1951 and began an affair. When they married, he was pursued by HUAC and she posed for photographs with the Committee, helping expedite his suspended sentence while he felt he was reenacting his own play. Even the fascists have to be entertaining. IV. Home. Miller talks about writing on the verge of embarrassment, revealing things that are essentially secret, even in symbolic fashion. He describes to Mike Wallace his failure to create significant work during the Monroe marriage with the throwaway line, I was taking care of her. He neglects to mention that she was paying his way and getting him writing jobs. However, he also declares, There’s no explaining a person like that. Terrible. Well. He describes her as being in some ways the most repressed person imaginable. He wrote The Misfits in tribute to her, allegedly, but of course we know that he and John Huston and Eli Wallach conspired to turn her character into a prostitute and it was Gable who saved her from that indignity. After the Fall in 1964 was crucified because it was such a direct attack on her, with Maggie her clear avatar, Quentin his. He was trying to make sense of the century’s most famous marriage. Following her death he married Inge Morath, the Look photographer whose father was a Nazi. Miller’s children from his first marriage say Morath made the Connecticut house (that Monroe bought for him) into a home. Do you think Dad had a weak spot for being adored? Rebecca asks his siblings about his marriages. It’s rhetorical. V. Out of Place. Other than The Price, the Sixties were not happy years for the playwright and the Seventies were downright barren not due to his output but due to the brutal critical reception in the US. Abroad, he was still admired. He had few friends. He was a very different man at home to the man interviewed on talk shows. It took Dustin Hoffman’s 1985 revival of Death of a Salesman for Miller’s stock to rise again. Rebecca’s younger brother was born in the mid Sixties with Down’s Syndrome and the Millers had him institutionalised. Miller did not acknowledge his existence or even visit him until he was an adult, leaving all that to his wife. Rebecca intended interviewing her father about this but never got around to it while he was alive. He says to his daughter that sons have it harder because there is an element of competition with the father. His older son Bobby produced the film version of The Crucible that introduced Rebecca to her husband, Daniel Day-Lewis. Teasing the man she knew from the man perceived in the wider world is what this film does best even if it’s limited by their relationship and the lack of emphasis on the content and style of his playwriting. Children create these definitions, says Miller. They have to. When asked what he wanted in his obituary, Miller responded, Writer.

Monkey Business (1952)

The language is confusing, the actions are unmistakable. Absent-minded chemist Dr. Barnaby Fulton (Cary Grant) is developing a pill that will defy the ageing process for the pharmaceutical company run by Oliver Oxley (Charles Coburn). When a loose chimpanzee mixes chemicals together that produce this effect, Fulton tries some on himself. This prompts him to act like a teenager, making passes at Oxley’s beautiful buxom secretary, Lois (Marilyn Monroe). Soon everyone, including Fulton’s wife, Edwina (Ginger Rogers), is feeling the effects of the formula and Edwina doesn’t enjoy the effects of youth when she finds herself reliving their honeymoon in the exact suite they spent their wedding night. When Barnaby goes AWOL she awakes to find a baby beside her in bed … Harry Segall’s story was adapted by director Howard Hawks, Ben Hecht, Charles Lederer and I.A.L. Diamond and has a lot of bright moments. It starts in stilted fashion however and the lack of a score (Hawks generally couldn’t abide them) leaves the unpunctuated action wanting. Monroe’s supporting role is underlined by Coburn’s declaration, Anyone can type! when he sends her to find someone to produce a letter; while Grant’s physicality is thrown into relief with a buzzcut. Their day out in his fast-moving roadster as he loses his sight behind his Coke-bottle glasses would be paid homage six years later with Tony Curtis and Monroe in Some Like It Hot. Never quite reaches the apex of screwball that Hawks himself had pioneered fifteen years earlier but it’s good for filling in a filmography that was at times sheer easygoing genius and there are points here when it recaptures the genre’s extraordinary vitality. Coburn and Monroe would be reunited with Hawks in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

Move Over Darling (1963)

Suppose Mr Arden’s wife came back, like Irene Dunne done. Did. Five years after her disappearance at sea, Nicky Arden (James Garner) is in the process of having his wife declared dead so he can marry his new fiancée Bianca (Polly Bergen) when Ellen (Doris Day) materialises and the honeymoon is delayed but Nick finds out Ellen wasn’t alone on the island after the shipwreck after all … A remake of one of the greatest screen comedies starring two of my favourite people? You had me at hello! This got partly remade as Something’s Got To Give with Marilyn Monroe and Dean Martin but got put on hold. Her premature death led to this iteration of Enoch Arden and My Favorite Wife, which was written by Samuel and Bella Spewack and Leo McCarey (upon whom Cary Grant modelled much of his suave screwball persona for their collaboration on The Awful Truth, another ingenious marital sex comedy.) Arnold Schulman, Nunnally Johnson and Walter Bernstein reworked that screenplay for the Monroe version (she agreed to star in it because of Johnson, and then George Cukor had it rewritten which upset her greatly); and then Hal Kanter and Jack Sher wrote this. We can blame Tennyson for the original. The set for the Arden home was the same from the Monroe version and it was based on Cukor’s legendarily luxurious Hollywood digs. We even get to spend time at the pool of the Beverly Hills Hotel. Garner and Day are brilliantly cast and work wonderfully well together, making this one of the biggest hits of its year (it was released on Christmas Day). They had proven their chemistry on The Thrill of it All and make for a crazy good looking couple. With Thelma Ritter as Nicky’s mom, Chuck Connors as the island Adam, and Don Knotts, Edgar Buchanan and John Astin rounding out the cast, we’re in great hands. The title song, co-written by Day’s son Terry Melcher and arranged by Jack Nitzsche, was a monster. Terrific, slick, funny blend of farce and sex comedy, this censor-baiting entertainment is of its time but wears it well. Directed by Michael Gordon.

The Apartment (1960)

Normally, it takes years to work your way up to the twenty-seventh floor. But it only takes thirty seconds to be out on the street again. You dig? Ambitious insurance clerk C. C. “Bud” Baxter (Jack Lemmon) permits his bosses to use his NYC apartment to conduct extramarital affairs in hope of gaining a promotion. He pursues a relationship with the office building’s elevator operator Fran Kubelik (Shirley MacLaine) unaware that she is having an affair with one of the apartment’s users, the head of personnel, Sheldrake (Fred MacMurray) who lies to her that he’s leaving his wife. Bud comes home after the office Christmas party to find Fran has taken an overdose following a disappointing assignation with Sheldrake … Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond were fresh off the success of Some Like It Hot when they came up with this gem: a sympathetic romantic comedy-drama that plays like sly satire – and vice versa. Reuniting one of that film’s stars (and a nasty jab at Marilyn Monroe using lookalike Joyce Jameson) with his Double Indemnity star (MacMurray, cast as a heel, for once) and adding MacLaine to the mix, they created one of the great American classics with performances of a lifetime. Bud can keep on keeping on as a slavering nebbish destined to be the ultimate slimy organisation man or become a mensch but he can’t do it alone, not now he’s in love. This is a sharp, adult, stunningly assured portrait of the battle of the sexes, cruelty, compromise and deception intact. With the glistening monochrome cinematography of Joseph LaShelle memorializing that paean to midcentury modernism, the architecture of the late Fifties office (designed by Alexandre Trauner), and an all-time great closing line (how apposite for a Wilder film), this is prime cut movie. The best Christmas movie of all time? Probably, if you can take that holiday celebration on a knife edge of suicidal sadness and bleakly realistic optimism. Rarely has a home’s shape taken on such meaning.