Oops. Geena Davis crashes out in The Long Kiss Goodnight.

Category Archives: Deer

Patrick (2018)

He grunts and snores but I’m kind of getting used to it. Sarah (Beattie Edmondson) is the underachieving secondary school English teacher whose boyfriend has just dumped her and she inherits her grandmother’s pugnacious pug Patrick despite despising dogs. While learning to live with him, she dates the socially awkward local vet (Ed Skrein), her BFF Becky (Emily Atack) persuades her to run a 5K even though she is totally unable to compete, she bitches about her superior older barrister sister and falls for Ben (Tom Bennett) who turns out to be the father of one of her students – whose parents’ divorce is sending her off the rails to the extreme point of not showing up for her GCSE English exam … Nobody covers themselves with glory in what is essentially a valentine to the loveliness of Richmond Upon Thames with its herds of deer and upwardly posh population. There is a laughable nod to social realism by having Sarah stumble upon her male students ripping the wheels off a car. This is so carelessly ‘written’ by Vanessa Davis that Skrein does not have a name: in the cast list he’s ‘Vet’. Edmondson’s real-life mother Jennifer Saunders turns up just in time to see her cross the finish line where Patrick has finally escaped a predatory cat. As bloody if. Patrick of course is not the point. Miaow! There’s a soundtrack of Amy Macdonald songs, which might please some people. Mildly directed by Mandie Fletcher, who directed Absolutely Fabulous: The Movie.

The Straight Story (1999)

You don’t think about getting old when you’re young… you shouldn’t. Retired farmer and widower in his 70s, WW2 veteran Alvin Straight (Richard Farnsworth) learns one day that his distant brother Lyle (Harry Dean Stanton) has suffered a stroke and may not recover. Alvin is determined to make things right with Lyle while he still can, but his brother lives in Wisconsin, while Alvin is stuck in Iowa with no car and no driver’s license because of his frailties. His intellectually disabled daughter Rose (Sissy Spacek) freaks out at the prospect of him taking off. Then he hits on the idea of making the trip on his old lawnmower, so beginning a picturesque and at times deeply spiritual odyssey across two states at a stately pace… I can’t imagine anything good about being blind and lame at the same time but, still at my age I’ve seen about all that life has to dish out. I know to separate the wheat from the chaff, and let the small stuff fall away Written by director David Lynch’s collaborator and editor Mary Sweeney and John E. Roach, this is perhaps the most ironically straightforward entry in that filmmaker’s output. He called it his most experimental movie and shot it chronologically along the route that the real Alvin took in 1994 (he died two years later). This is humane and simple, beautifully realised (DoP’d by Freddie Francis) with superb performances and a sympathetic score by Angelo Badalamenti. A lyrical tone poem to the American Midwest, the marvellous Farnsworth had terminal cancer during production and committed suicide the following year. His and Stanton’s scene is just swell, slow cinema at its apex. The worst part of being old is rememberin’ when you was young

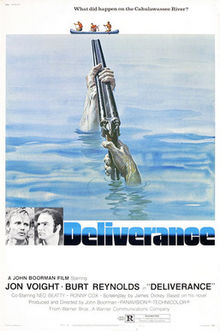

Deliverance (1972)

Now you get to play the game. Four Atlanta-dwelling friends Ed Gentry (Jon Voight), Lewis Medlock (Burt Reynolds), Bobby Trippe (Ned Beatty) and Drew Ballinger (Ronny Cox) decide to get away from their jobs, wives and kids for a week of canoeing in rural Georgia, going whitewater rafting down the Cahulawassee river before the area is flooded for the construction of a dam. When the men arrive, they are not welcomed by the backwoods locals, who stalk the vacationers and savagely attack them, raping one of the party. Reeling from the ambush, the friends attempt to return home but are surrounded by dangerous rapids and pursued by an armed madman. Soon, their canoe trip turns into a fight for survival… You don’t beat it. You don’t beat the river. Notorious for the male rape and praised for the Duelling Banjos scene that happens in the first scene-sequence, this film went into production without insurance and with the cast doing most of their own dangerous stunts. Reynolds is simply great as Lewis the alpha male daredevil with the shit-eating grin and a way with a bow and arrow. This is a role that transformed his screen presence into box office. His sheer beauty affirms the audience’s faith in male potential: when he has an accident we are devastated. What will happen now to the clueless bunch being hunted by the inbred hillbilly loons? Insurance? I’ve never been insured in my life. I don’t believe in insurance. There’s no risk. Voight is the straight guy Ed who has to pick up the action baton, Bobby dithers and Drew may have been shot – or not. Author James Dickey adapted his own novel with director John Boorman and appears in the concluding scenes as the Sheriff. Like most of Boorman’s work there are narrative problems – mostly resting in a kind of empty sensationalism that however disturbing never truly penetrates, with visuals substituting for the environmental story. This gives a whole new meaning to the term psychogeography. Squeal like a pig! The cast are perfection, with Beatty and Cox making their screen debuts having been discovered doing regional theatre. Finally, Voight’s character is haunted, the experience converted into a horror trope in the penultimate shots. The power rests in the juxtaposing of man and nature, modernity versus the frontier, conjoined with the spectre of primitive redneck violence and its consequences on hapless male camaraderie where survival is the only option once civilisation is firmly out of reach. Danger is only a boat ride away. A gauntlet to weekend warriors everywhere, it’s quite unforgettable. Sometimes you have to lose yourself ‘fore you can find anything

Elle (2016)

Shame isn’t a strong enough emotion to stop us from doing anything at all. Believe me. Perverse, funny, strange, blackly comic and at times surreal, this is a film like few others. It opens on a black screen as Michèle Leblanc (Isabelle Huppert) is raped by a masked man. She gets up, cleans herself and bathes and carries on as though nothing has happened. At work she is the one in control – it’s her company and she deals in the hyper-real, trying to make video games more experiential, the storytelling sharper, the visuals more tactile. She is attacked in a cafe by a woman who recognises her as her father’s lure – as a child she her dad murdered a slew of people and he’s an infamous serial killer, turned down for release yet again at the age of 76 and it’s all over the news: there’s a photo taken of her as a blank-eyed ten year old which haunts people. Her mother is a plastic surgery junkie shacked up with another young lover. Her ex-husband (Charles Berling) is broke and tries to pitch her an idea for a game. Her loser son has supposedly knocked up a lunatic girlfriend (the eventual baby is not white) and needs money for a home. Elle is sleeping with the husband of her partner Anna (Anne Consigny). She likes to ogle her neighbour Patrick (Laurent Lafitte). Now as she gets text messages about her body she tries to figure out who among her circle of acquaintances could have raped her – and then when it happens again she unmasks him and starts a relationship of sorts following a car crash (a deer crosses the road, not for the first time in a 2016 film). This is where the edges of making stories, power, control, reality, games and the desire for revenge become blurred. Adapted from Patrick Dijan’s novel Oh by David Birke and translated into French by Harold Manning, this is Paul Verhoeven’s stunning return to form, with Huppert giving a towering performance as a wily, strong, vulnerable, tested woman – she owns her own company and handles unruly employees using a sympathetic snitch but cannot control her family members and their nuttiness. You can’t take your eyes off her, nor can the camera. While she tries to figure out how to regain her composure (she rarely loses it, even while she’s getting punched in the face) she also sees a way in which she might obtain pleasure. In some senses we might see a relationship with Belle de Jour: Michèle is the still centre of a world in which crazy is normal. It’s shot to reflect this, with the video game and the animation of her made illicitly by one employee the only visual extremes. The assaults (there’s more than the first, when she gets the taste for it) are conventionally staged. She has turned the tables on her rapist – he is undone by her desire for sex. This is all about role play. When Michèle finally decides to cut the cord on all the loose ends in her life it brings everything to a satisfying conclusion as she regains her balance – her role as CEO assists her manage her own narrative minus any generic tropes. Now that’s clever. Oh! The audacity! What a great film for women in a very contemporary take on noir and the notion of the femme fatale. Big wow. I killed you by coming here

Captain Fantastic (2016)

I’m writing down everything you say – in my mind. Disillusioned anti-capitalist intellectual Ben Cash (Viggo Mortensen), his absent wife Leslie (she’s in a psychiatric facility) and their six children live deep in the wilderness of Washington state. Isolated from society, their kids are being educated them to think critically, training them to be physically fit and athletic, guiding them in the wild without technology and demonstrating the beauty of co-existing with nature. When Leslie commits suicide, Ben must take his sheltered offspring into the outside world for the first time to attend her funeral in New Mexico where her parents (Frank Langella and Ann Dowd) fear for what is happening to their grandchildren and Ben is forced to confront the fact that the survivalist politics he has imbued in his offspring may not prepare them for real life… This starts with the killing of an animal in a ritual you might find in the less enlightened tribes. (Why did killing a deer become a thing a year ago?) Ben is teaching his eldest son Bodevan (George McKay) to be a man. But this is a twenty-first century tribe who are doing their own atavistic thing – just not in the name of Jesus (and there’s a funny scene in which they alienate a policeman by pretending to do just that) but that of Noam Chomsky. “I’ve never even heard of him!” protests their worried grandfather. Hearing the words “Stick it to the man!” coming out of a five year old is pretty funny in this alt-socialist community but the younger son in the family Rellian (Nicholas Rellian) believes Ben is crazy and has caused Leslie’s death and wants out. Ironically and as Ben explains at an excruciating dinner with the brother in law (Steve Zahn) it was having children that caused her post-partum psychosis from which this brilliant lawyer never recovered. This stressor between father and younger son drives much of the conflict – that and Leslie’s Buddhist beliefs which are written in her Will and direct the family to have her cremated even though her parents inter her in a cemetery which the kids call a golf course. And Bodevan conceals the fact that he and Mom have been plotting his escape to one of the half dozen Ivy League colleges to which he’s been accepted. The irony that Ben is protecting his highly politicised kids from reality by having them celebrate Chomsky’s birthday when they don’t even know what a pair of Nikes are and have never heard of Star Trek is smart writing. Everything comes asunder when there are accidents as a result of the dangers to which he exposes them. This is a funny and moving portrait of life off the grid, with Mortensen giving a wonderfully nuanced performance as the man constantly at odds with the quotidian whilst simultaneously being a pretty great dad. McKay is terrific as the elder son who’s utterly unprepared for a romantic encounter in a trailer park. It really is tough to find your bliss. As delightful as it is unexpected, this is a lovely character study. Written and directed by Matt Ross.

A Cure for Wellness (2016)

Do you know what the cure for the human condition is? Disease. Because only then is there hope for a cure. An ambitious young executive Lockhart (Dane DeHaan) is sent to retrieve his company’s CEO Pembroke (Harry Groener) from an idyllic but mysterious “wellness center” at a remote location in the Swiss Alps. He soon suspects that the spa’s miraculous treatments are not what they seem and the head doctor Volmer (Jason Isaacs) is possessed of a curiously persuasive zeal and, rather like Hotel California, nobody seems able to leave. Lockhart’s sighting of young Hannah (Mia Goth) drives him to return. When he begins to unravel the location’s terrifying secrets, his sanity is tested, as he finds himself diagnosed with the same curious illness that keeps all the guests here longing for the cure and his company no longer wants anything to do with him because the SEC is investigating him – and is that Pembroke’s body floating in a tank? … Part bloody horror, part satire, indebted equally to Stanley Kubrick, mad scientist B movies and Vincent Price, this has cult written all over it. Co-written by director Gore Verbinski with Justin Haythe, with his proverbial visual flourishes, this is one 141-minute long movie that despite its outward contempt for any sense of likeability, actually draws you in – if you’re not too scared of water, institutions, eels or demonic dentists. Isaacs has a whale of a time as the equivalent of a maestro conducting an orchestra who dispatches irritants with a flick of a switch or insertion of an eel. DeHaan gets paler by the scene. Wouldn’t you? The one thing you do not want to do is drink the water! A man cannot unsee the truth!

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017)

I can’t say anything defamatory and I can’t say fuck piss or cunt. After months have passed without a culprit in her daughter’s murder case, divorcee Mildred Hayes (Frances McDormand) hires three billboards leading into her town with a controversial message directed at William Willoughby (Woody Harrelson) the town’s chief of police. When his second-in-command, Officer Dixon (Sam Rockwell), a racist immature mama’s boy with a penchant for violence – gets involved, the battle is only exacerbated. Willoughby’s pancreatic cancer diagnosis is known around town so the locals don’t take kindly to Mildred’s action. Dixon’s intervention with Red (Caleb Landry Jones) who hired out the advertising is incredibly violent – he throws him out a first floor window – and it’s witnessed by Willoughby’s replacement (Clark Peters) and gets him fired. When Mildred petrol bombs the sheriff’s office she doesn’t realise Dixon is in it and he sustains terrible burns but resolves to become a better person and resume the investigation into the horrific murder of Mildred’s teenage daughter … Martin McDonagh’s tragicomedy touches several nerves – guilt, race, revenge, justice. The beauty of its construction lies in its allowing so many characters to really breathe and develop just a tad longer than you expect. Those little touches and finessing of actions make this more sentimental than the dark text might suggest. That includes difficult exchanges between Mildred and her son Robbie (Lucas Hedges) and the wonderful relationship between Willoughby and his wife Anne (the great Abbie Cornish) which really expand the premise and lift the lid on family life. Yet the sudden violence such as that between Mildred and her ex Charlie (John Hawkes) still contrives to shock. There are two big character journeys here however and as played by McDormand and Rockwell the form demands that they ultimately come to a sort of detente – and it’s the nature of it that is confounding yet satisfying even if it takes a little too long and concludes uncertainly, just adding to the moral quagmire. A resonant piece of work.

Julieta (2016)

The abject maternal has long been a strong component of Spanish auteur Pedro Almodovar’s oeuvre and in this striking adaptation of three Alice Munro stories from Runaway he plunders the deep emotional issues that carry through the generations. On a Madrid street widowed Julieta (Emma Suarez) runs into Beatriz (Michelle Jenner) who used to be her daughter’s best friend. Bea tells her she met Antia in Switzerland where she’s married with three children. Julieta enters a spiral of despair – she hasn’t seen Antia since she went on a spiritual retreat 12 years earlier and she now abandons lover Lorenzo (Dario Grandinetti) on the eve of their departure for Portugal. She returns to the apartment she lived in with Antia when the girl was an adolescent and hopes to hear from her, the birthday postcards having long ceased. We are transported back to the 1980s when on a snowy train journey to a school in Andalucia Julieta (now played by Adriana Ugarte) resisted the advances of an older man who then committed suicide and she had a one-night stand with Xoan (Daniel Grao). She turns up at his house months later and his housekeeper Marian (the heroically odd Rossy de Palma) tells her his wife has died and he’s spending the night with Ava (Inma Cuesta). Julieta and Xoan resume their sexual relationship and she tells Ava she’s pregnant and is advised to tell Xoan. And so she settles into a seaside lifestyle with him as he fishes and she returns with her young child to visit her parents’ home where her mother is bedridden and her father is carrying on with the help. Years go by and she wants to return to teaching Greek literature, which has its echoes in the storytelling here. The housekeeper hates her and keeps her informed of Xoan’s onoing trysts with Ava; her daughter is away at camp; she and Xoan fight and he goes out fishing on a stormy day and doesn’t return alive. This triggers the relationship between Antia and Bea at summer camp which evolves into Lesbianism albeit we only hear about this development latterly, when Bea tells Julieta that once it become an inferno she couldn’t take it any more and Antia departed for the spiritual retreat where she became something of a fanatic. Julieta’s guilt over the old man’s death, her husband’s suicidal fishing trip and her daughter’s disappearance and estrangement lead her to stop caring for herself – and Lorenzo returns as she allows hope to triumph over miserable experience. There are moments here that recall Old Hollywood and not merely because of the Gothic tributes, the secrets and deceptions and illicit sexual liaisons. The colour coding, with the wonderfully expressive use of red, reminds one that Almodovar continues to be a masterful filmmaker even when not utterly committed to the material; and if it’s not as passionate as some of his earlier female dramas, it’s held together by an overwhelming depiction of guilt and grief and the sheer unfathomability of relationships, familial and otherwise. Suarez and Ugarte are extremely convincing playing the different phases of Julieta’s experiences – how odd it might have been in its original proposed version, with Meryl Streep in the leading role, at both 25 and 50, and filming in English. I might still prefer his early funny ones but a little Almodovar is better than none at all.

Bambi (1942)

A recent documentary about Walt Disney barely revealed anything about the man. For that, you watch the films. This is the high point of his achievements: an adaptation of a book by Austrian writer Felix Salten, it is the story of a young fawn (a white tail) whose life in the meadow and the forest is mirrored by the changing seasons, his friendships with woodland creatures, death, dealings with hunters, all animated impressionistically and vividly. I can barely watch this because tears prick my eyes from the moment it starts and those memories of my first childhood viewing never leave me. It is simply stunning, moving, funny, brilliant and devastating, underscored by classical music tropes and songs. Directed by David Hand, leading a team of exquisitely gifted sequence directors, writers and artists, produced by Walt Disney. A film for the ages.