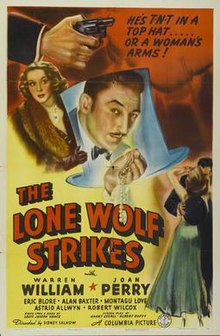

He travels fastest who travels alone. Michael Lanyard (Warren William) the retired and reformed gentleman crook known as the Lone Wolf, is pottering with his aquarium when his old friend, Stanley Young (Addison Richards) appears to enlist his aid in recovering a priceless pearl necklace that has been stolen from his murdered friend, Phillip Jordan. Young tells Lanyard that Jordan had found out that Binnie Weldon (Astrid Allwyn) who had been leading the old geezer on with her accomplice Jim Ryder (Alan Baxter) and they stole the pearls and replaced them with fakes. Lanyard agrees to switch the pearls back again and his long-serving butler and crafty assistant Jamison (Eric Blore) is more than relieved to return to a semblance of normality. However Lanyard is hampered in his task by the misguided meddling of Delia Jordan (Joan Perry) the murdered man’s daughter. Posing as foreign fence and old nemesis Emil Gorlick (Montagu Love), Lanyard gets the pearls from Binnie and Ryder but after he turns them over to Stanley, his old friend is found murdered and the pearls have gone missing. Stanley’s murder throws suspicion on Lanyard, and to clear himself of the crime, he must find both the murderers and the necklace. To accomplish this, Lanyard tricks the killers into believing that they have the fake pearls and Delia has the real ones. Much to Delia’s dismay, Lanyard’s trap nets her, suitor Ralph Bolton (Robert Wilcox) and Alberts (Harland Tucker) the man who hired Bolton to keep an eye on the pearls. After convincing Alberts that he has the genuine pearls, Lanyard leads the killers on a merry chase … I’m jolly well fed up of being a gentleman’s gentleman to a lot of sardines. A crime comedy series based on the characters created by Louis Joseph Vance is based on the one-time popular trope of the gentleman thief a la Raffles (created by E.W. Hornung in 1898, 19 years after the Lone Wolf emerged). The film adaptations were being made as early as 1917 and Warren William’s stint of nine films had commenced with the previous year’s entry, The Lone Wolf Spy Hunt. He had previously played a number of nasty businessmen in the pre-Code era as well as being the first screen incarnation of Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason and the second Sam Spade in Satan Was a Lady, a version of The Maltese Falcon. I loathe fish! Part of the series’ great attractiveness is the presence of Blore, the butler of choice at the time, whose put downs are world class. It’s only when you’re immersed in your fish that you disappoint me, Sir. He would feature in eleven of the films overall, concluding with The Lone Wolf in London in 1947. With twist upon twist (who can keep up with who’s got what set of pearls?), fast moves, witty dialogue and delightful actors, it doesn’t hurt that the slyly original story is by that gifted scribe Dalton Trumbo, who would of course be blacklisted and deprived of Academy Awards won under the names of writers who fronted for him, as regaled in the biopic Trumbo. He wrote both Kitty Foyle and A Bill of Divorcement the same year but for RKO, whereas this was made at Columbia. The screenplay is by Harry Segall & Albert Duffy. In the meantime, this series went from strength to strength and a seriously ill William would eventually be replaced by Gerald Mohr in 1946 prior to his premature death from multiple myeloma in 1948. Sadly his wife died within a few months of his demise. The charming leading lady Perry married Columbia Studio boss Harry Cohn and her career as a supporting actress ceased in 1941 which is a real shame considering all she does here. Highly entertaining. Directed by Sidney Salkow. I’m such a changeable person. I plan on doing one thing and suddenly do another