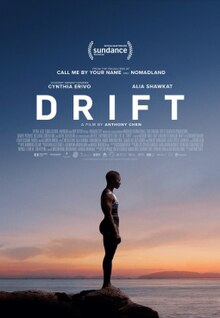

Plane. Ferry. Boat. Luck. Jacqueline Kamara (Cynthia Erivo) is living hand to mouth in a Greek seaside town, scavenging for food, sleeping in a cave, avoiding direct contact with people except when she realises with a stolen bottle of olive oil she can earn a few euros giving massages to sun lovers. The unwanted attentions of beach trader Ousmane (Ibrahima Ba) lead her to take more care with her routine. She finds herself on the route of a cultural tour led by Callie (Alia Shawkat) an American married to a Greek man who offers friendship and eventually kindness which overwhelms Jacqueline, who’s pretending she’s a tourist on holiday with her husband. Following a fall in which she gets a concussion, she wakes up in hospital and Ousmane is in the same ward: he quietly advises her to run. At Callie’s apartment she finally recounts the story of her family’s murder at the hands of terrorists in Liberia where her father was a Government minister and just froze when the kids arrived with guns and machetes … You might be sitting here just minding your own business then all of a sudden, rape and pillage. Adapted by Susanne Farrell and Alexander Maksik from his 2013 novel A Marker to Measure Drift, this commences as a quietly observational drama, with Jacqueline picking her way along the beach in Greece, avoiding interactions, with flashbacks to a different life, when she had a full head of hair, travelling on a train with girlfriend Helen (Honor Swinton Byrne), staying with Helen’s family in London then returning to her own family in Charles Taylor’s Liberia. She is shocked into thoughts of her recent past by the attempt of a black man to engage her in conversation. If you feel lonely you must not come back. Is it clear to you? Erivo is not the most sympathetic of performers and her character’s inability to communicate her trauma makes this a tricky watch. Not a lot happens yet she has clearly experienced something terrible to reduce her to this hard-scrabble subsistence. The town where she finds herself is clearly not accustomed to the presence of black people and she and Ousmane (and his sidekick) stick out like sore thumbs. Slowly, she begins to be stripped of her defences – literally, when she’s in Callie’s bathtub and screams as Callie takes her clothing to launder it: she doesn’t want to part with it. Then, explaining that she’s lost most of her memory, she tells her story and the buildup from the periodic flashbacks culminates in the tale of the murderous terror caused by her country’s conflict. There are a lot of dots to join. Shawkat provides a warm repository for the information, a shoulder to cry on in a film about storytelling. Ironically, considering Callie’s role, delivering classical Greek tales of destruction and bloody history to visitors, there is no precision about the circumstances of Jacqueline’s situation (we must infer that it’s the 2003 civil war) yet it too has the contours of Greek tragedy and horrific violence. There’s a compelling narrative here that isn’t fully dramatised in a screenplay that’s more allusive than explanatory. Erivo is one of the film’s producers and she performs a wonderful song (It Would Be) with Laura Mvula over the end credits. Directed by Anthony Chen. There were so many of them